writer and engineer, specialising in work with community groups and

grassroots campaigns. His website is www.fraw.org.uk/mei.

On 17 October 2013, Ben Emmerson – the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on ‘the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism’ – submitted his interim report[1] on the use of drone strikes to the UN General Assembly. A few days later, Human Rights Watch issued their own report[2] on the use of counter-terrorist drone strikes in Yemen. While both these reports clinically outline the use of automated machines to launch military action at a distance, both fail to encompass the precise nature of how this system functions. Looking at the issue of drones and robotic military technology at the point where people are killed is like trying to understand an iceberg by looking at the part which sticks out of the water – it tells you very little about the nature of the whole system you are trying to study.

It may seem a jump from drones to the revelations about surveillance by US whistle-blowers Edward Snowden[3] and Chelsea Manning,[4] but what both they and the UN’s Special Rapporteur are describing are the samesystem. When we look at the ‘networked state’, surveillance, cyber warfare, the use of military drones, and the machines which enable all those systems to function together, they are one and the same. And when we consider the use of drones for targeted strikes against ‘insurgents’, again, considering recent military doctrines, it is difficult to separate the both the intelligence hardware which directs those strikes, and the long-term technology, foreign and security policies which have created it.

The 1980s: The first silicon war machines

To understand the significance of what is taking place today we begin not with the endpoint – armed military drones – but with the device which makes this entire system possible – the programmable microprocessor. If we look back over the last 40 years of the evolution of the microprocessor we might believe that we’ve come a long way – from pocket calculators to today’s internet and smart phones. In fact, the power of the microprocessor has a long way yet to run, and could – in the space of just a decade or so – make the capabilities of today’s ‘intelligent’ devices seem like the clunky operation of those 1970s pocket calculators.

—————————————————————————————————-

[1] Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, Ben Emmerson, United Nations, 18 September 2013 –http://www.fraw.org.uk/files/peace/un_sphr_2013.pdf

[2] Between a Drone and Al-Qaeda: The Civilian Cost of US Targeted Killings in Yemen, Human Rights Watch, 22 October 2013 – http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/yemen1013_ForUpload.pdf

[3] Edward Snowden, Guardian On-line news archive – http://www.theguardian.com/world/edward-snowden

[4] Chelsea Manning, Guardian On-line news archive – http://www.theguardian.com/world/chelsea-manning

———————————————————————————————-

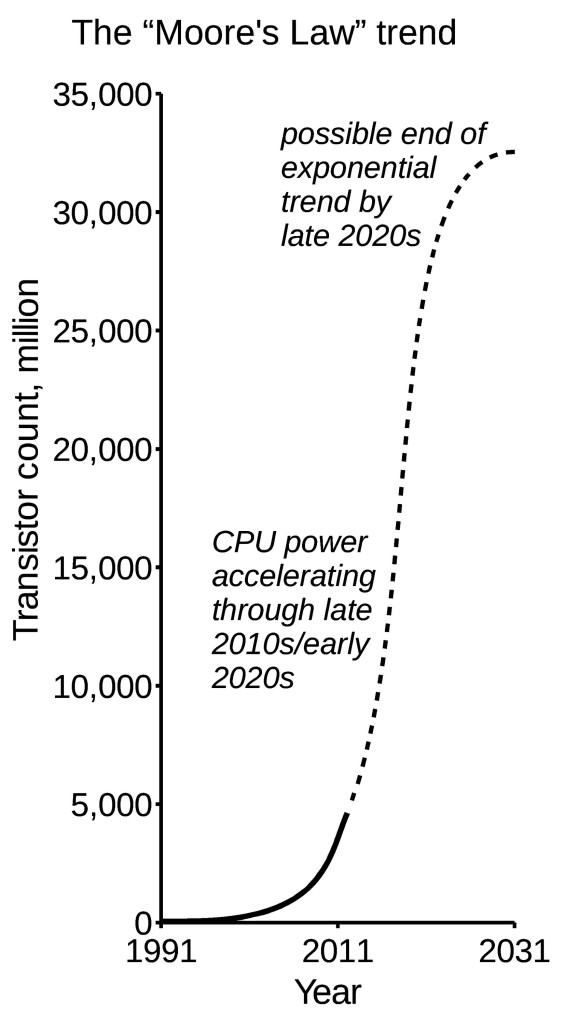

In 1965, one of the founders of the semiconductor revolution, Gordon Moore, wrote a paper which predicted that the number of transistors (the transistor count) which could be packed into these devices would double every 18 months or so as the technologies to manufacture them developed. In turn, the power of these devices would double over the same period. That trend, now called ‘Moore’s Law’,[5] has described the growth of computer processing power, data storage, and the capacity of data communications ever since it was made in the 1960s.

In 1965, one of the founders of the semiconductor revolution, Gordon Moore, wrote a paper which predicted that the number of transistors (the transistor count) which could be packed into these devices would double every 18 months or so as the technologies to manufacture them developed. In turn, the power of these devices would double over the same period. That trend, now called ‘Moore’s Law’,[5] has described the growth of computer processing power, data storage, and the capacity of data communications ever since it was made in the 1960s.

Despite the ultimate limitations on packing transistors into microprocessors,[6] Moore’s Law might continue to apply for at least another decade or two. That being the case – as shown in the graph of The Moore’s Law trend – the power of computer systems will dramatically accelerate over the next decade. In turn, the capabilities of those new systems to collect, process, interpret and report data will double every two years or so.

Now turn that principle towards our recent knowledge about state surveillance or the use of autonomous drones… and perhaps then you’ll see where this phenomena is heading.

The computer networks which laid the foundations of both the military and civil telecommunications and data network can be traced back[7] to the 1960s. However, the US military did not seriously engage with the power of computer networks until nearly 20 years later. In 1983, Ronald Reagan had initiated the Strategic Defense Initiative,[8]commonly called the ‘Star Wars’ project. It was a failure – primarily because it tried to achieve goals which were way beyond the capabilities of the technology which existed at the time.

From that failure the US military saw the potential of these technologies to assist their existing missions, and in the early 1990s the doctrine of ‘full spectrum dominance’ was created – a belief that computers, communications, and both ground- and space-based surveillance systems could achieve complete control over military operations. In 1996 this vision was outlined by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff as the Joint Vision 2010[9] – later updated as Joint Vision 2020[10] in May 2000.

———————————————————————-

[5] ‘Moore’s Law’, Croughtonwatch, January 2014 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/croughtonwatch/files/wikipedia-moores_law.html

[6] Michio Kaku: Tweaking Moore’s Law and the Computers of the Post-Silicon Era, YouTube, 13th April 2013 – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bm6ScvNygUU

[7] ‘History of the Internet’, Croughtonwatch, January 2014 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/croughtonwatch/files/wikipedia-history_of_the_internet.html

[8] ‘Strategic Defense Initiative’, Croughtonwatch, January 2014 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/croughtonwatch/files/wikipedia-strategic_defense_initiative.html

[9] Joint Vision 2010, US Joint Chiefs of Staff, July 1996 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/files/peace/us_dod_1996.pdf

[10] Joint Vision 2020, US Joint Chiefs of Staff, May 2000 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/files/peace/us_dod_2000.pdf

—————————————————————————-

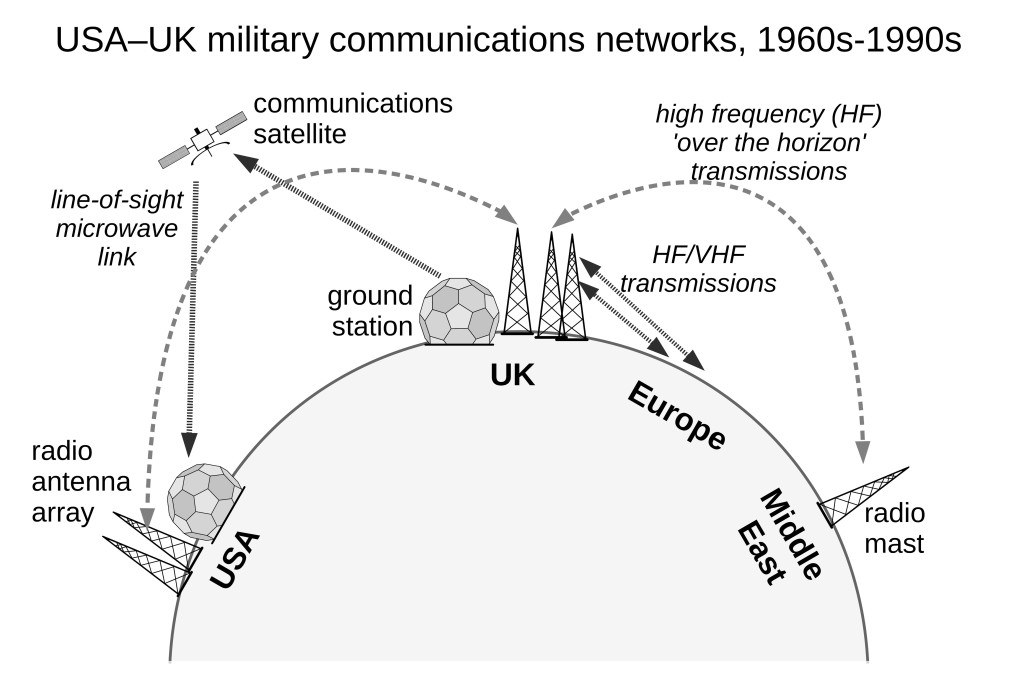

From the 1980s, the military establishments of the developed nations funded new digital communications networks to create global systems for command, surveillance, and ultimately to direct offensive action. For the USA, the geographical location of their bases in the UK was a key part of the operation of this global system. During the Cold War, military communications had relied on a network of radio stations using conventional high-frequency voice and radio-teletype (telex) links, with some low capacity satellite links. In Britain, US communications bases provided a staging post for communications routed from Europe, North Africa and the Middle East to the USA. British bases also provided a point to intercept radio communications from Eastern Europe and Russia. With the end of the Cold War it looked like these sites would become redundant, but the full-spectrum dominance doctrine gave them a new purpose in the global communications network.

The 1990s: Military theory meets evolving technology

Military academics have come to see warfare as evolving over different historical eras, each of which saw competing powers undergoing a race for tactical supremacy. During the late 1980s/early 1990s their vision was that we were moving into the fourth generation of warfare.[11] Fourth generation warfare is all about the decentralisation of conflict. The destructive potential of modern technology means that standing armies gain little from engaging directly, and so instead powers seek to engage each other indirectly by a variety of means. Rather than military foes meeting in high intensity conflict, this doctrine foresees conflict as a more drawn-out process involving political, economic and social subversion which seeks to degrade the ability of the state to function. More importantly, no longer are ‘powers’ limited to nation states. Any organised group, using the resources and technologies created by post-World War Two industrialisation, can now engage in this global battleground.

It was this changing view of military conflict which led the major military powers: to focus far more on intelligence and surveillance – because that is what’s required to monitor the activities of decentralised or ‘insurgent’ forces; and to focus far more on small-scale offensive or policing actions – because the large-scale conflict of whole armies is no longer viable. From this perspective, it is possible to see the rationale for both the evolution of today’s mass surveillance networks, and also the development of systems such as pilot-less drone aircraft.

The difficulty is that by viewing conflict as an essentially ideological struggle between small groups, rather than as an organised engagement between nation states, it is inevitable that these new technologies would be deployed against civilian populations – and even against the citizens of the states concerned. By polarising political or economic debates between the interests of ‘the state’ versus ‘everyone else’, democracy is no longer a dialogue between alternative ideas, but an ongoing militarised struggle between opposing ideologies.

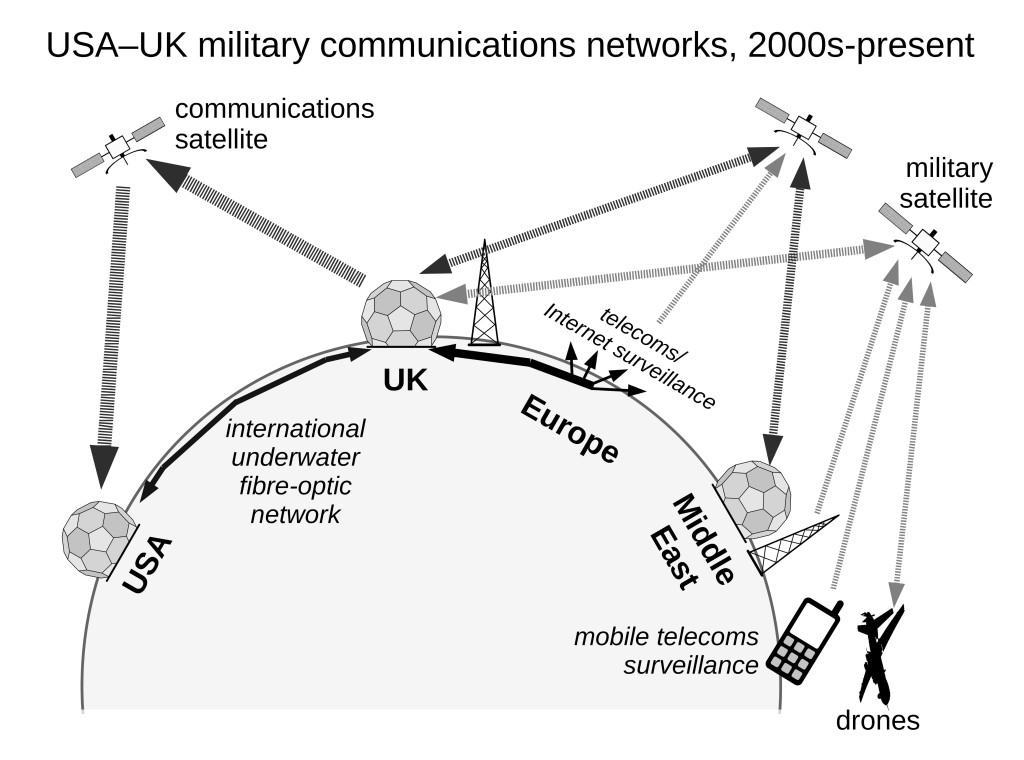

Rather than the low capacity high-frequency radio links of the Cold War, these new systems utilise many more satellite-based systems (the USA launched over 200 military satellites between 1984 and 2013) – in effect militarising the control of space in accordance with the full-spectrum dominance doctrine. Microwave satellite communications only work by line of sight, and to span the globe satellite ground-stations have to be set up to supervise the flow of information from one region to another. Britain, strategically placed between the USA, Europe and the Middle East, acts as a way-station for US military/security networks. In addition, US agencies can access the European microwave and fibre-optic communications networks directly from the UK’s telecommunications infrastructure to carry out surveillance of digital information traffic on the European continent. Once again, within this new post-Cold War strategy, Britain is a key link in the chain of command and control – between the analytical capabilities of USA’s foreign and domestic security agencies, and the peripheral information collection gathering capabilities of the global network. The US bases at Menwith Hill, Croughton and Alconbury provide not just a conduit for phone calls and emails, but also the command systems for drones, and the information generated by the various global monitoring and surveillance systems. The cooperation agreement between the UK and US intelligence agencies[12] also means the resources of British security agencies, such as GCHQ in Cheltenham, supply a valuable back-up to the USA’s own systems.

The roll-out of new digital networks by military and civil agencies during the 1990s revolutionised communications and intelligence. When all communications – be it your telephone, email, credit card transactions or Internet browsing – are reduced to binary data, then all forms of economic and social activity in society are potentially available for surveillance. Also, because this is digital information, rather than having to engage many expensive human operators, banks of computers can quickly and cheaply sift these large quantities of information looking for patterns of activity which are deemed ‘valuable’. Using digital technological rather than human-based systems, individuals can be tracked and their activity monitored to assess their potential threat to the state – enabling far larger scales of surveillance to be carried out than were possible before.

In the final instance, when individuals are considered a ‘threat’, they can be geographically located and then eliminated using the weapons systems linked into these networks. It is these ‘targeted killings’ which have recently caused some of the greatest civilian casualties[13], and created some of the greatest enmity to the use of remote-controlled war machines. One of the early examples of targeted killing was the assassination of the Chechen president Dzhokhar Dudayev in 1996; the Russian military tracked his satellite phone and then, when it was confirmed he personally was speaking on the phone, launched missiles onto that location. Today, with the increased sophistication of these technologies, and the deployment of pilot-less aircraft which can stay airborne for long periods, both the surveillance and offensive capacities of the most technologically advanced states have grown significantly; and will continue to do so whilst the key component which underpins those developments – the microprocessor – increases its operating capacity.

————————————————————————-

[11] ‘Fourth-generation warfare’, Croughtonwatch, January 2014 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/croughtonwatch/files/wikipedia-fourth_generation_warfare.html

[12] ‘UKUSA Agreement’, Croughtonwatch, January 2014 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/croughtonwatch/files/wikipedia-uk_usa_agreement.html

[13] ‘Targeted killing’, Croughtonwatch, January 2014 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/croughtonwatch/files/wikipedia-targeted_killing.html

—————————————————————————

The 2000s: The war against terror, mass surveillance and the rise of the drones

A significant milestone in the development of these systems was the attack on the World Trade Centre in September 2001. That not only legitimated the military’s previous focus on non-state-based or ‘insurgent’ groups, it also created an environment where the states could justify the introduction of new surveillance laws (such as the Patriot Act in the USA; or the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, Terrorism Act 2000 andSerious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 in the UK) and spending ever greater amounts on security and surveillance.

As military and security agencies rolled out their new intelligence gathering capabilities in the wake of 9/11, and as the subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq created new problems, this experience fed back into the development of a new understanding of how technology could be used by military and security agencies to ‘project force’ around the globe. In the USA, the military policies of the 1990s developed into new strategies forInformation Age Warfare,[14] decentralising military operations,[15] and Network-Centric Warfare.[16] These updated the ideas of ‘full spectrum dominance’ to take advantage of the new computer networks and mobile telecommunications.

Central to the development of these ideas was a new agency set-up by US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld – The Office for Force Transformation. Although it was disbanded five years later, this office was instrumental in getting technology companies and the military working together to develop new automated systems – even to the point where the technical staff of these companies were deployed with troops in action to develop and perfect their products. This reinforced the push towards the greater use of technology by the military, and led to a new emphasis on the use of automated systems in conflict zones – now generally called ‘drones’.

Whilst we might use the term ‘drone’ to identify the infamous Predator or Reaper unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) there are in fact over 500 land, air and on/under-water ‘drones’ in production or development by the five leading manufacturing states (USA, UK, Israel, Russia and China) – and many countries are now buying these technologies as these states develop an export market for their products[17].

——————————————————————————-

[14] Understanding Information Age Warfare, David S. Alberts, Command and Control Research Programme, US Department of Defense, 2001 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/files/peace/alberts_2001.pdf

[15] Power to the Edge: Command and Control in the Information Age, David S. Alberts, Richard E. Hayes, Command and Control Research Programme, US DoD, 2003 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/files/peace/alberts_hayes_2003.pdf

[16] The Implementation of Network-Centric Warfare, Office of Force Transformation, US Department of Defense, 2005 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/files/peace/dod_ncw_2005.pdf

[17] Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century, P.W. Singer, Penguin Books, 2011. ISBN 9780 1431 1684 4. £9.99.

—————————————————————————-

Contrary to the popular media depiction, drones come in all shapes and sizes. Some of the smallest aerial drones, designed for surveillance, will fit into your hand. Others, such as the PackBot, used by soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, are designed to scout ahead in dangerous situations (for example, a PackBot was sent in to the damaged reactor buildings following the Fukushima nuclear disaster to provide video surveys), fit into a rucksack. Larger and heavily armed ground-based drones, such as the TALON, are being developed for offensive use as scouts or sentries – primarily in urban areas. The largest drones, like the Predator and Reaper, are self-guiding aircraft. However, one of the fast developing areas of technology is self-guided land vehicles. Originally a military concept, these are now being rapidly developed for civilian use – and will be licensed for use on the UK’s roads by the end of 2013,[18] and Nissan expect to be manufacturing driver-less cars for sale by 2020.[19]

The important factor in the development of all these systems is that it is primarily private companies developing these systems for the military. Whilst these projects are initially Government-funded, the companies involved stand to make their greatest profits not from the military applications, but from their greater potential in the civil sector. If you look at the economics of driver-less vehicles, what will fund the roll out of this technology will be replacing the human driver with a fully automated ‘delivery machine’ – or, for example, self-driving taxis. Likewise the computer software developed by security agencies for mass surveillance has parallels within the ‘big data’ applications now being developed for use by commercial companies – and often it is the same companies involved in the production of systems for use by security agencies.

The Edward Snowden affair has been a very public example of the close relationship between the civil corporate IT sector and the use of ‘big data’ by the security services. Snowden worked for the civilian IT contractor Booz Allen Hamilton, working as a private analyst for the CIA and NSA. Following 9/11, the US Department for Homeland Security conceived a project called Total Information Awareness, intended to collect data from across the USA on the activities of every citizen. In 2003 the US Congress withdrew funding for that project, precisely because of concerns about the implications for civil liberties. Snowden saw that the objectives of that project were instead carried out by a covert NSA project codenamed PRISM. Another, XKeyscore, carried out similar operations on individuals globally. A similar project run by the British GCHQ, Tempora, sifted data intercepted from global telecommunications networks and then tracked large numbers of individuals. Whilst these projects had been cleared by the oversight committees within the agencies concerned, elected officials in government – even at Cabinet level[20] – were excluded from having knowledge of their existence or operation. Whether or not these projects broke either US, UK or European law is still a matter of official debate, and may take years of both public investigations and private litigation to resolve.

—————————————————————————————

[18] Driverless cars to be tested on UK roads by end of 2013, BBC News On-line, 16 July 2013 – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-23330681

[19] Nissan: We’ll have a self-driving car on roads in 2020, CNN, 28 August 2013 – http://edition.cnn.com/2013/08/27/tech/innovation/nissan-driverless-car/index.html

[20] Prism and Tempora: the cabinet was told nothing of the surveillance state’s excesses, Chris Huhne, Guardian On-line, Sunday 6 October 2013 – http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/06/prism-tempora-cabinet-surveillance-state

—————————————————————————

Of greater concern for society in general are the increasingly close links between the military and security services, defence and IT companies, and the wider body of corporate interests who those security companies service. As a result of these links the boundary between the military, the public and the private has becoming increasingly blurred. For example, in 2008, when climate change protesters were planning an action at a power station, officials at the UK’s Department of Business gave police intelligence files to the plant’s operators, EON.[21] Likewise, Canadian security officials routinely hold briefings for Canadian corporations to disclose information on rival foreign companies discovered during their surveillance operations.[22] In the USA – as recently outlined in the documentary Gasland, Part 2 – companies involved in shale gas (or ‘fracking’) are advised by former US military personnel[23] on the use of military ‘psychological operations’ against both protesters, and the communities they’re drilling around. More recently in the USA, freedom of information requests by the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund[24] revealed that the FBI and Department for Homeland Security were producing briefings on the Occupy movement for American corporations.

Returning to the change in military doctrines outlined earlier, that conflict is now viewed as existing between the state and small groups who might for various reasons ‘disagree’ with it, it’s important to consider to what extent that this might become a self-fulfilling prophecy. As Nietzsche said, ‘Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster.’ Is the establishment seeing enemies because it wants to, or simply because these groups exercise their democratic rights to disagree?

Nafeez Ahmed, director of the Institute for Policy Research and Development, considers that such shifts in security strategy are the result of an uncertain political environment[25]. The fact that economic stagnation, resource depletion and climate change might create civil unrest is pushing the establishment towards a greater fear of the citizens of the developed world – just as much as it might fear the insurgent groups of the developing world. When the state mistrusts its citizens, does that create the very crisis it perceives to exist?

——————————————————————————-

[21] Secret police intelligence was given to E.ON before planned demo, Matthew Taylor and Paul Lewis, Guardian On-line, Monday 20 April 2009 – http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2009/apr/20/police-intelligence-e-on-berr

[22] CSEC defends practices in wake of Brazilian spy reports, Steven Chase, The Globe and Mail, Wednesday 9 October 2013 – http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/nothing-illegal-about-spying-on-brazil-agency-chief-says/article14774444/

[23] Fracking and Psychological Operations: Empire Comes Home, Steve Horn, Truthout, Thursday 8 March 2012 – http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/7153:fracking-and-psychological-operations-empire-comes-home

[24] FBI Documents Reveal Secret Nationwide Occupy Monitoring, Partnership for Civil Justice Fund, 22 December 2012 – www.justiceonline.org/commentary/fbi-files-ows.html

[25] Pentagon bracing for public dissent over climate and energy shocks, Nafeez Ahmed, Guardian On-line, 14 June 2013 – http://www.theguardian.com/environment/earth-insight/2013/jun/14/climate-change-energy-shocks-nsa-prism

————————————————————————————-

Tomorrow: What future for civil democracy in a cybernetic world?

Over the history of the modern state, war has required a general consensus within the population. This is because war is not only expensive, it also requires the active support of the public to provide the military personnel who engage in conflict. That same need for unanimity provides a check on the power of the state. That’s not just because the state needs the people to fight for it; the debate over conflict allows for a broader range of views – let’s call it ‘common sense’ – to be applied to the operations of both the military, police and security services.

Replacing people with machines breaks that check on administrative excess – in many ways. That’s not just an issue with drones: the use of networked surveillance in the more affluent nations has parallels to the use of drone strikes in poorer nations. To begin to consider how, we need to examine what is happening today.

The United Nation’s Special Rapporteur’s interim report on the use of drone strikes lays out a complex picture of how automated systems are used to enact what is, put simply, extra-judicial killing – a sentence of death without the due process of an impartial trial. The Special Rapporteur does not say that the use of a drone strike is always unlawful. But when used outside a declared war zone, for example within Pakistan or Yemen, it is questionable as to whether such action is legal or is a war crime[26]. Human Rights Watch’s report on drone strikes in Yemen states that some attacks were clear violations of international humanitarian law because they struck only civilians or used indiscriminate weapons; whilst others may have violated the laws of war because the individual attacked was not a lawful military target or the attack caused disproportionate civilian harm.

—————————————————————————-

[26] Drone strikes by US may violate international law, says UN, Owen Bowcott, Guardian On-line, Friday 18 October 2013 – http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/18/drone-strikes-us-violate-law-un

——————————————————————————

According to the UN Rapporteur’s report, Yemeni government permission had been obtained for all strikes: while in Pakistan permission for strikes came from the military establishment, although whether that has the support of elected ministers is a matter of debate. In Pakistan, unconfirmed reports put the death toll at around 2,200, with over 600 serious injuries. However, because of the problems collecting data in these areas, the Government could only confirm 600 civilian deaths, with a further 200 regarded as ‘non-combatants’. The report also covers the use of drones in Libya, Iraq, Gaza, Somalia and Afghanistan, and whilst in all areas it is accepted that civilian casualties have resulted from drone strikes, the problems of accurate data collection, or identifying targets, mean that producing confirmed figures is very difficult. The report identifies that the greatest problem in testing the legality of drone strikes is that it requires command accountability for their use, but that, ‘the single greatest obstacle to an evaluation of the civilian impact of drone strikes is lack of transparency, which makes it extremely difficult to assess claims of precision targeting objectively’.

In terms of the impacts of recent Western military action, drones have thus far caused only a small fraction of the total casualties. However, as we move forward from today what might we expect to change? Already opposition groups in the Middle East are working on counter-measures to the use of drones – not just aerial drones, but also the ground-based systems used for scouting buildings in urban areas and defusing bombs. States such as Iran are using captured drones, or parts of them, to try and develop their own drone technologies. Some have already speculated that it is only a matter of time before we see conflicts involving the use of drones by both sides, or a significant terrorist incident using an ‘insurgent drone’.[27]

As technology advances, it is arguably only a matter of time before an ‘insurgent drone’ arises. For example, in the US and Europe there is already amateur interest in, and readily available technology for the construction of ‘DIY drones’.[28] The difficulty is, whilst it is possible to outline ‘unconventional’ drone attacks, there are a series of technical barriers which have to be crossed to get to that point. But as time passes, and the required technology improves and becomes more readily available, it is arguably not an implausible scenario.

Unfortunately, due to the speed and complexity of technology, the principal method of countering insurgent drones is with more drones – and then we enter a wholly different world. That’s because to allow drones to counter the use of other drones we have to give our drones far greater autonomy. Technically we are still some distance from that point, but not far. Even so, the issue still arises as to how – in perhaps five or ten years time – a future UN Special Rapporteur might investigate the accountability and transparency of the targeting decisions of a machine intelligence. Where networks of machines are involved, for example where a machine responsible for detection and tracking sends instructions to a strike drone, it becomes an even more complex problem.

If we want an example of what full autonomy entails then we should examine the recent history of global stock and commodity exchanges. In automated financial (or ‘algorithmic’) trading reaction time is everything. In a mirror of the arms race, financial institutions have to use automated trading because ‘ everybody else’ uses it, and they are all in a perpetual battle to ‘win’ the technological race surrounding automated trading. The problem, from the evidence of a decade or so of this practice,[29] is that while these systems work acceptably for much of the time, they are inherently unstable and prone to sudden, unexpected and aberrant behaviour. Basically, we let the machines loose and unsurprisingly, they don’t behave like people!

————————————————————————

[27] Threat of Terrorism Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Technical Aspects, Eugene Miasnikov, Center for Arms Control, Energy and Environmental Studies, June 2004 (translated into English, March 2005) –http://www.armscontrol.ru/uav/report.htm

[28] How I Accidentally Kick-started the Domestic Drone Boom, Chris Anderson, Wired Magazine, 22 June 2012 – http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2012/06/ff_drones/all/

[29] Black box traders are on the march, Telegraph On-line, 27 August 2006 – http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/2946240/Black-box-traders-are-on-the-march.html

Knight Capital Says Trading Glitch Cost It $440 Million, Dealbook, New York Times, 2 August 2012 – http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/08/02/knight-capital-says-trading-mishap-cost-it-440-million/

Stock plunge raises alarm on algo trading, Reuters, 6th May 2010 – http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/05/06/us-market-selloff-idUSTRE6455ZG20100506

Hoax Shows Growth in Algorithmic Trading, Wall Street Journal, 6th May 2013 – http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2013/05/06/the-twitter-hoax-shows-growth-in-algorithmic-trading/

Too Fast to Fail: Is High-Speed Trading the Next Wall Street Disaster?, Mother Jones, January/February 2013 – http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/02/high-frequency-trading-danger-risk-wall-street

———————————————————————————

Would drones behave any differently? If a trading machine malfunctions, a bank loses a few hundred million; when drones malfunction, many people might die. For example, consider the incident in 1983 when a Russian missile defence operator disregarded his instruments warning of a US missile strike because he didn’t believe they were working correctly[30] – what would a machine have done?

In December 2013, the US Department of Defense published its “Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap” – a detailed programme of how the greater use of remotely-controlled drone technologies, surveillance capabilities and high-power computing facilities would be rolled out to support all sections of America’s armed forces and security establishments.[31] And of course, where American leads, other major military power follow. Therefore irrespective of concerns about the viability or long-term efficacy of these technologies, defence establishments around the globe are now locking themselves into this pattern of supra-human-based technological development.

If we look at the evolving language which the military has used to describe the purposes of their technology since the 1990s – from Star Wars, across two decades to drones and cyberwarfare – it is about command anddominance. At the same time the notion of who these systems are meant to ‘oppose’ has shifted from whole nation states towards small groups of people. And whether those people are in poor societies being bombed by drones, or in affluent societies having their lives monitored, has little practical difference – it’s the same underlying information and intelligence machinery which administers and co-ordinates that process. Likewise, whether or not the extra-judicial killing of suspects is legal under international law, or whether the mass surveillance of the populace by their government is lawful by their own national laws, is still being argued over today – and may be so for some time. That is because the alternate outcome to the military/security strategy of command and dominance would be engagement and dialogue – and whilst that seems antithetical to their expressed democratic principles, such a strategy is not open for debate within the leading Western states right now (perhaps not even with their own people).

Irrespective of how we resolve this problem – and right now there are many obstacles to any solution – set aside that objective and return to the beginning of this chapter. The implication of Moore’s Law is that by the end of this decade the power of the machines involved in that system is likely to quadruple; and before we reach the limits of this trend we might see computing capacities 30 times greater than they are today. Quite literally, comparing today’s drones to the drones of 2025 might be like comparing those 1970s pocket calculators to today’s mobile phones.

—————————————————————————————

[30] Stanislav Petrov: The man who may have saved the world, BBC News, 26 September 2013 – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-24280831

[31] Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap, US Department of Defense, December 2013 – http://www.fraw.org.uk/files/peace/us_dod_2013.pdf

—————————————————————————————-

The real issue here is not simply the use of machines by the state, or the controls over their lethality. The greatest flaw in the whole machine is the governing human element; and certainly – as shown by the debate over the use of drones or the disclosures over surveillance by Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning – our fundamental problem is not one of control, it is of oversight, transparency and accountability. Solving that has little to do with machines and silicon diodes, but has much to do with how we value ourselves, our society, and how our human system chooses to govern itself.

Recommended reading:

– P.W. Singer, Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century (London: Penguin Books, 2011)

– Benjamin Medea & Barbara Ehrenreich, Drone Warfare: Killing by Remote Control (London: Verso Books, 2013)

– Daniel J. Solove, Nothing to Hide: The False Trade-off Between Privacy and Security (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2013)

Recommended video:

– P.W. Singer: Military robots and the future of war, TED, February 2009 – http://www.ted.com/talks/pw_singer_on_robots_of_war.html

– The Secret Drone War, BBC Panorama, 10 December 2012 –

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ov5mmVIGrJc

– ‘Protest Policy of Full Spectrum Dominance’, workshop with Bruce Gagnon, April 2013 – http://www.youtube.com/embed/84EY-mOYjyM

– The Trigger Effect (series 1, episode 1), James Burke’s Connections, BBC, 1978 – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WgOp-nz3lHg

– Michio Kaku: Tweaking Moore’s Law and the Computers of the Post-Silicon Era, YouTube, 13 April 2013 – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bm6ScvNygUU

Web sites:

– Dronewars – http://dronewars.net/

– Drone Campaign Network – http://dronecampaignnetwork.wordpress.com/

– Campaign for the Accountability of American Bases – http://www.caab.org.uk/

– CND UK: Ground the Drones Petition –

http://www.cnduk.org/campaigns/anti-war/ground-the-drones-petition

– Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space – http://www.space4peace.org/

– DIY Drones – http://diydrones.com/

Nuclear weapons crime in the UK has been reported to Thames Valley Police.

Nuclear weapons crime in the UK has been reported to Thames Valley Police.